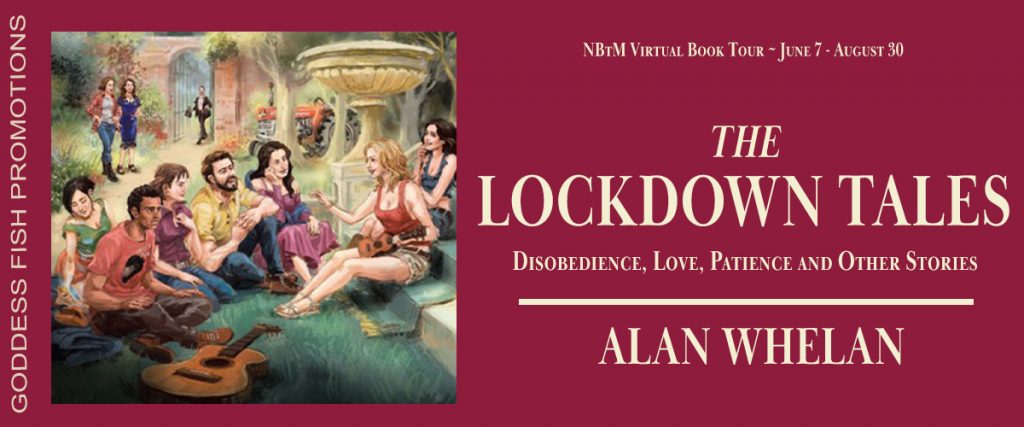

This post is part of a virtual book tour organized by Goddess Fish Promotions. Alan Whelan will be awarding a $15 Amazon/BN GC to a randomly drawn winner via rafflecopter during the tour. Click on the tour banner to see the other stops on the tour.

The Lockdown Tales is a book written during the Covid-19 lockdown. It’s unusual, possibly unique, in being written while the pandemic is still uncontrolled, and we still don’t know what the outcome will be.

The most important literary model for The Lockdown Tales is Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, which was written against the background of the bubonic plague outbreak of 1347 and 1348. It follows ten people who leave Florence for the countryside to escape the plague, where they tell each stories to keep each others’ spirits up.

But Boccaccio wrote after the plague had passed, beginning his book in 1351 and finishing in 1353. Boccaccio, like Daniel Defoe when he wrote his A Journal of a Plague Year in 1720-odd, about a plague that blazed in 1665, had the luxury of being able to look back on something that was over, and its history known. I didn’t have that, but I wanted to write something for people who were in much the same situation as me.

I began The Lockdown Tales on 12 March 2020, when it was obvious that everybody’s life was about to change dramatically and that politicians weren’t up to facing, let alone dealing with, the challenges that it brought. I finished on 21 October 2020, when there was still no way of knowing how this pandemic would end. Or even develop.

I thought a lot, when I started The Lockdown Tales, about a cheerful old man I saw waving toilet rolls outside my local supermarket. He became my lodestar. Panicked idiots and greedy people who expected to make profits had stripped the supermarket shelves of toilet paper and a lot of food staples. This man waited in the carpark, giving away toilet rolls to people, especially older people, who’d lost out in the supermarket rush.

He reminded me that a crisis like a pandemic brings out selfish idiocy, but it also brings out some of the best in human nature, as thoughtful people take practical steps to look after and support each other, including strangers. When I wrote I kept him in mind.

The Lockdown Tales has Covid-19 as its background, and that means that it includes, death, damage and mourning, but it’s not in any sense a misery memoir, or the fictional equivalent. It follows ten people, a more diverse group than Boccaccio’s, who leave the city when the pandemic first arrives and join together in the countryside where, like Boccaccio’s ten characters, they flirt, forming or losing relationships, support each other, make music and above all tell each other stories.

As in the Decameron, the stories are generally about life before, and perhaps after, the pandemic. There are bawdy stories, adventure stories, stories about people trying to do the right thing by each other in hard times. They are sometimes satirical and sometimes sad, but most often they are laugh-out-loud funny. One thing about the humour: Shakespeare makes jokes about lazy servants or stupid commoners, while Boccaccio punches up: the butts of his jokes are people with power, in one form or another. I’m on Boccaccio’s team.

I’ve read The Lockdown Tales at least 500 times, as any writer must, hunting for typos, bad writing or boring writing, and even after that it still made me laugh. If a book can withstand that sort of reading, then it’s alive.

The Lockdown Tales isn’t a didactic book. I didn’t write it to push a message. I wrote it to reflect life in all its ordinariness and weirdness, and tell the very best stories that I could write. Its settings range from the super-continent Pangea 350 million years ago to medieval Italy, to China in 1920 and New Guinea in 1944, to Sydney just after the Beatles played, and Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere today. I can guarantee that any reader will find something they like.

But there’s a principle behind the story-telling that I kept in mind throughout, like that cheerful man giving out the toilet rolls: courage, cleverness, kindness and hope are better than their alternatives.

Seven women and three men leave the city to avoid a pandemic. They isolate together in a local farm, where they pass the time working, flirting, eating, drinking, making music and above all telling stories. It happened in Florence in 1351, during the Plague, and gave us Boccaccio’s Decameron.

Seven hundred years later, in Australia, it happens again. The stories are very different, but they’re still bawdy, satirical, funny and sometimes sad, and they celebrate human cleverness, love, courage and imagination.

“Alan Whelan brings us a clever, sensual and sometimes poignant collection of stories that would make Boccaccio proud”

– Tangea Tansley, author of A Question of Belonging“An old frame for a sharp new snapshot of contemporary Australia”

– Leigh Swinbourne, author of Shadow in the Forest

Enjoy an Excerpt

It was late and getting cold by the time Margo’s story was done. I reflected that she’d come a long way, in the three weeks she’d been here. She’d got close to Sue and Stuart, and they’d helped her believe that she could come back from Harry’s death.

Stuart and Danny pushed my barbecue back to the house, with Sue and Margo helping to keep it steady. This time it didn’t tip over.

Bran and Astrid stayed close to the fire, which had died down from a bonfire to a campfire. Jayleen and Bob stayed close. Bob had slept through most of the stories and was now awake, and enthralled by the night, the lake and the fire. I heard Astrid say, “The beast with three backs!” She punched Bran, amused.

He put his arm round her and drew her close. Bob climbed onto Astrid, so Jayleen took her place beside Bran, and he put his other arm round her. The night was cold. I had no idea if he really did want a threesome, but if he did I thought his chances were still close to zero.

Grace had relented after a stoned night of mostly ignoring Amelia. They walked back to the house together. I didn’t fancy Amelia’s chances much, either. But I knew that I’d make no declarations to Amelia unless her infatuation with Grace had been resolved and gone.

I collected empty bottles and put them in my pack. I probably missed some, but I’d check the ground in the morning. I shrugged the pack on and trudged back to the house.

When I reached the verandah I turned and took one last look at the fire and the lake. Astrid was kissing Bran, with intent, and Jayleen had snuggled in tight against his back. I wondered if I’d underestimated his chances. Though I still didn’t know if he had any threesome intentions. I decided it didn’t matter and I didn’t care, though no doubt it would mean a lot to them.

I shut the door behind me and went up to my bed.

About the Author: Alan Whelan lives in the Blue Mountains of NSW, Australia. He’s been a political activist, mainly on homelessness, landlord-tenant issues and unemployment, and a public servant writing social policy for governments. He’s now a free-lance writer, editor and researcher.

Alan Whelan lives in the Blue Mountains of NSW, Australia. He’s been a political activist, mainly on homelessness, landlord-tenant issues and unemployment, and a public servant writing social policy for governments. He’s now a free-lance writer, editor and researcher.

His story, There Is, was short-listed for the Newcastle Short Story Award in June 2020, and appeared in their 2020 anthology. His story, Wilful Damage, won a Merit Prize in the TulipTree Publications (Colorado) September 2020 Short Story Competition, and appears in their anthology, Stories that Need to be Told. It was nominated by the publisher for the 2021 Pushcart Prize.

His book The Lockdown Tales, using Boccaccio’s Decameron framework to show people living with the Covid-19 lockdown, is now on sale in paperback and ebook.

His novels, Harris in Underland and Blood and Bone are soon to be sent to publishers. He is currently working on the sequel to The Lockdown Tales and will then complete the sequel to Harris in Underland.

Alan Whelan co-wrote the book, New Zealand Republic, and has had journalism and comment pieces published in The New Zealand Listener and every major New Zealand newspaper, plus The Australian and the Sydney Morning Herald.

He wrote two books for the NZ Government: Renting and You and How to Buy Your Own Home. His stories also appear in Stories of Hope, a 2020 anthology to raise funds for Australian bushfire victims, and other anthologies.

His website is alanwhelan.org. He tweets as @alannwhelan.

His phone number is +61 433 159 663. Enthusiastic acceptances and emphatic rejections, also thoughtful questions, are generally sent by email to alan@alanwhelan.org.

Buy the book at Amazon, Amazon CA, Amazon AU, Bookshop, , Barnes and Noble, Book Depository, Kobo, Smashwords, or iBooks.

Thanks for hosting!

Great excerpt and giveaway. 🙂

Hi Cali!

I should probably explain about that extract that “Bob” is Jayleen’s four-year-old son, and so, while there are some sweet confusions, under the moonlight, it’s not an orgy. It’s a quieter thing.

This sounds good!

Thanks from me too!

I’m not 00% of the etiquette and rules with this, but I’m very happy to answer any questions anyone has for me.

Thank for reading! (And, seriously, I think think you’ll enjoy The Lockdown Tales. It’ll make you laugh, but also think.

This sounds like a very good book.

A very interesting story

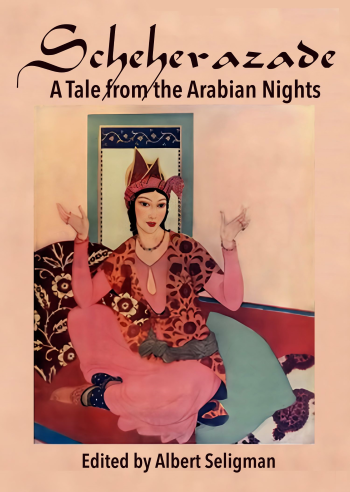

I love the artwork on the cover. Thanks for the giveaway!